The History of the Royal Observatory Edinburgh

Astronomy has been taught at the University of Edinburgh since its foundation in 1583. Initially there was no permanent observatory and students used portable instruments. There were several attempts to establish an observatory during the eighteenth century, but these foundered until the first observatory was built on Calton Hill in central Edinburgh towards the end of the century. The Observatory received a Royal Charter in 1822, making it a dual institution, responsible to both the University and directly to the Crown. The new Royal Observatory remained on the Calton Hill site for most of the nineteenth century, where it largely pursued a programme of traditional positional astronomy. In the 1890s the Observatory moved to its present site on Blackford Hill, on the outskirts of Edinburgh, where the emphasis of its work shifted to the then-new astrophysics, studying the composition and constitution of the stars. The Observatory has long been associated with the development of new instrumentation and techniques, particularly since the Second World War. In the 1990s a major reorganisation of the way that astronomy in the UK was organised consolidated this tradition by establishing the Astronomy Technology Centre on the site. Meanwhile the University's astronomy department, operating under the rubric of the Institute for Astronomy and co-located on the site has become one of the principal astronomy groups in the UK.

Astronomy in the Early University

Seventeenth Century examination questions in astronomy from the University of Edinburgh.

Seventeenth Century examination questions in astronomy from the University of Edinburgh.

Edinburgh University has taught astronomy since its foundation in 1583 as the 'Tounis College'. Like other Medieval and Renaissance universities the curriculum was based on the Trivium of verbal arts and Quadrivium of numerate arts, the latter comprising mathematics, geometry, astronomy and music. Again like the other ancient Scottish universities, and their continental counterparts, it operated the 'regenting system' whereby a tutor or 'regent' taught all of a student's classes throughout his years at the university. During the 1600s this system was gradually augmented, and eventually replaced, by the 'professorial' system, in which professors were appointed to teach (or 'profess') a single subject. Particularly in the present context, in 1620 the senior Regent of Philosophy was made 'public professor of mathematics'. However in these early years professors also had to undertake the duties of regents, and the distinction between the two roles is not always clear. A notable early Professor of Mathematics was James Gregory (1638-1675), appointed in 1674. He was an eminent mathematician who had produced a novel design for a reflecting telescope and of whom much was expected. Tragically, he died, aged less than 40, within a year of his appointment, reputedly having been struck by blindness while showing students the moons of Jupiter through a telescope.

Another prominent holder of the Chair of Mathematics was Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746), who made a number of important contributions to the discipline. He was appointed in 1725 and held the post until his death in the mid-century. One of his innovations was a course in 'experimental philosophy', which included observations of the Moon, planets and stars from telescopes mounted on the flat roof of the old University Library (this building, long demolished, occupied what is now the north-east corner of Old College).

Another prominent holder of the Chair of Mathematics was Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746), who made a number of important contributions to the discipline. He was appointed in 1725 and held the post until his death in the mid-century. One of his innovations was a course in 'experimental philosophy', which included observations of the Moon, planets and stars from telescopes mounted on the flat roof of the old University Library (this building, long demolished, occupied what is now the north-east corner of Old College).

Founding of the Calton Hill Observatory and the Chair of Astronomy

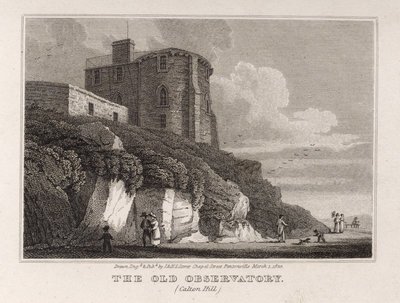

The Old Observatory Building on Calton Hill, completed in 1792.

The Old Observatory Building on Calton Hill, completed in 1792.

Maclaurin, and later the Edinburgh telescope-maker James Short (1710-68), a protege of Maclaurin, tried to establish a permanent observatory for use by students and the public. These plans took many years to come to fruition, but in 1776 a foundation stone was laid on the Calton Hill site, on land provided by the City Council. The Observatory building was completed in 1792, much reduced from the original plans.

In 1811 a group of interested private individuals founded the Astronomical Institution of Edinburgh to raise funds for a new or extended observatory on Calton Hill. Their fund-raising was successful and in 1818 work commenced on the new observatory, to a neo-classical design by William Playfair. During his visit to Edinburgh in 1822 George IV conferred a Royal Charter on the still-incomplete observatory, which hence became a Royal Observatory, responsible to both the University and the Crown. Its Directors were subsequently styled Astronomer Royal for Scotland. Construction was completed in 1824 and an engraving on the wall notes:

That a renowned city should not any longer lack the facilities for the pursuit of the fairest and grandest of sciences.

Meanwhile, some years earlier in 1785, the University had founded a Chair of Practical Astronomy, principally to provide instruction in navigation for officers serving on merchant ships operating out of the nearby port of Leith. The Chair was a Regius one, that is, it was a Royal appointment. The first incumbent was Robert Blair (1748–1828), though the choice was not a happy one. He was principally a medical and naval man (and continued to make significant contributions to these fields), but he refused to give lectures at the University on the, not entirely unreasonable, grounds that he had neither an observatory nor instruments. He was away from Edinburgh for long periods of time and died in post in 1828.

In 1811 a group of interested private individuals founded the Astronomical Institution of Edinburgh to raise funds for a new or extended observatory on Calton Hill. Their fund-raising was successful and in 1818 work commenced on the new observatory, to a neo-classical design by William Playfair. During his visit to Edinburgh in 1822 George IV conferred a Royal Charter on the still-incomplete observatory, which hence became a Royal Observatory, responsible to both the University and the Crown. Its Directors were subsequently styled Astronomer Royal for Scotland. Construction was completed in 1824 and an engraving on the wall notes:

That a renowned city should not any longer lack the facilities for the pursuit of the fairest and grandest of sciences.

Meanwhile, some years earlier in 1785, the University had founded a Chair of Practical Astronomy, principally to provide instruction in navigation for officers serving on merchant ships operating out of the nearby port of Leith. The Chair was a Regius one, that is, it was a Royal appointment. The first incumbent was Robert Blair (1748–1828), though the choice was not a happy one. He was principally a medical and naval man (and continued to make significant contributions to these fields), but he refused to give lectures at the University on the, not entirely unreasonable, grounds that he had neither an observatory nor instruments. He was away from Edinburgh for long periods of time and died in post in 1828.

The Royal Observatory on Calton Hill

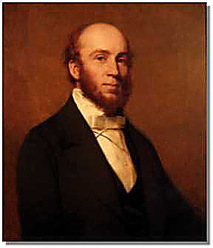

Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900).

Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900).

The Royal Observatory remained on Calton Hill for most of the rest of the nineteenth century. In 1834, some six years after the death of Robert Blair, Thomas Henderson (1798-1844) was appointed to the joint post of Regius Profesor of Practical Astronomy and Director of the Royal Observatory, thus becoming the first Astronomer Royal for Scotland. Originally from Dundee, he had previously been the Director of the Royal Observatory of the Cape of Good Hope. Henderson is mostly remembered for making the first measurements that lead to the determination of the distance to a star, a long sought-after result in astronomy. He did not, however, make the first determination of such a distance; that honour belongs to the German astronomer and mathematician Friedrich Bessel (1784-1846) who measured the distance to 61 Cygni in 1838. Henderson's determination was derived from observations that he had made some years earlier while at the Cape, as part of the routine work of the Observatory. He did not appreciate their significance and deferred analysing them, only completing and presenting his results, for the star Alpha Centauri, shortly after Bessel had published.

Henderson had never enjoyed robust health and died in 1844 at the early age of 46. His successor was Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), who was appointed the second Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1846, having previously served as Assistant Director at the Cape Observatory. Piazzi Smyth remains the longest serving Astronomer Royal for Scotland and is probably the most colourful character to have held the post. He was a polymath who worked in many fields, despite never having been to university. He was an accomplished artist and an early and enthusiastic exponent of the then-new technique of photography. He contributed to the development of both spectroscopy and meteorology. In 1864 he executed what was then the most accurate survey of the Great Pyramid of Giza and became the first person to photograph inside it.

Amongst astronomers Piazzi Smyth is best remembered for an 1856 expedition to Tenerife during which he demonstrated the advantages of high-altitude mountain-top sites for astronomical observations. Such sites, with their clear skies and steady air, are now ubiquitous for major observatories, but in the nineteenth century their advantages were not appreciated. Another innovation was the Edinburgh time service started in 1853: a time-ball dropped from the Nelson Monument on Calton Hill at 1:00 pm every day, so that ships in Leith could synchronise their chronometers. In 1861 the service was augmented with a time-gun fired from the ramparts of Edinburgh castle at the same hour. These services continue to this day and the time-gun, in particular, is a popular tourist attraction.

Henderson had never enjoyed robust health and died in 1844 at the early age of 46. His successor was Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), who was appointed the second Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1846, having previously served as Assistant Director at the Cape Observatory. Piazzi Smyth remains the longest serving Astronomer Royal for Scotland and is probably the most colourful character to have held the post. He was a polymath who worked in many fields, despite never having been to university. He was an accomplished artist and an early and enthusiastic exponent of the then-new technique of photography. He contributed to the development of both spectroscopy and meteorology. In 1864 he executed what was then the most accurate survey of the Great Pyramid of Giza and became the first person to photograph inside it.

Amongst astronomers Piazzi Smyth is best remembered for an 1856 expedition to Tenerife during which he demonstrated the advantages of high-altitude mountain-top sites for astronomical observations. Such sites, with their clear skies and steady air, are now ubiquitous for major observatories, but in the nineteenth century their advantages were not appreciated. Another innovation was the Edinburgh time service started in 1853: a time-ball dropped from the Nelson Monument on Calton Hill at 1:00 pm every day, so that ships in Leith could synchronise their chronometers. In 1861 the service was augmented with a time-gun fired from the ramparts of Edinburgh castle at the same hour. These services continue to this day and the time-gun, in particular, is a popular tourist attraction.

The Move to Blackford Hill

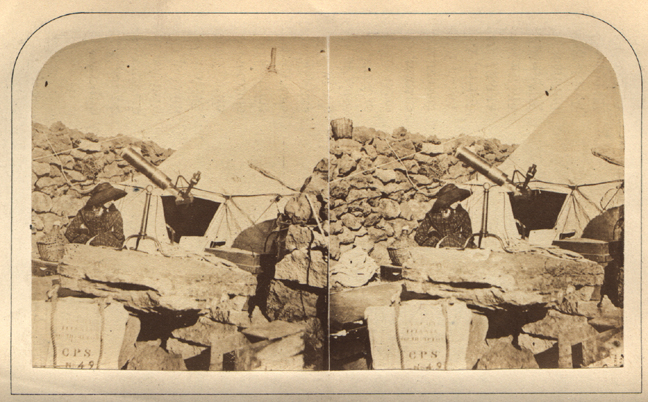

The West Tower of the new Observatory under construction on Blackford Hill.

The West Tower of the new Observatory under construction on Blackford Hill.

When Piazzi Smyth retired in 1888 the Calton Hill Observatory was in a poor state. It had been underfunded for years and had outdated equipment on a poor site, surrounded by the growing city of Edinburgh. It offered instruction to few students. Around the same time a Royal Commission was reporting on the Scottish Universities. It recommended that the Royal Observatory be disestablished and the buildings and equipment simply handed over to the University. At this point there was a dramatic development. James Ludovic Lindsay (1847-1913), the twenty-sixth Earl of Crawford, hearing of this suggestion during a debate in the House of Lords resolved 'it shall not be'. The Earl of Crawford was a keen astronomer who ran a private observatory on the family estates at Dun Echt, Aberdeenshire. This establishment was a serious and significant institution which produced important work. The Earl of Crawford offered all the instruments in his observatory as a gift to the nation if the Government would build a replacement for the Calton Hill Observatory to house them. He also made a gift of his unique and magnificent astronomical library.

The Government accepted the offer and in 1889 Ralph Copland (1837-1905), who had previously been Chief Astronomer at Dun Echt, was appointed Regius Professor and the third Astronomer Royal for Scotland. A new site was selected on Blackford Hill, a public park on the edge of Edinburgh, with darker skies away from the city centre. Construction started in 1892 and was completed in 1895, with a formal opening on 7 April 1896 by Lord Balfour of Burleigh, the Secretary of State for Scotland. The Observatory remains on this site, with the original buildings largely intact and is still on the southern edge of the city.

The Government accepted the offer and in 1889 Ralph Copland (1837-1905), who had previously been Chief Astronomer at Dun Echt, was appointed Regius Professor and the third Astronomer Royal for Scotland. A new site was selected on Blackford Hill, a public park on the edge of Edinburgh, with darker skies away from the city centre. Construction started in 1892 and was completed in 1895, with a formal opening on 7 April 1896 by Lord Balfour of Burleigh, the Secretary of State for Scotland. The Observatory remains on this site, with the original buildings largely intact and is still on the southern edge of the city.

The Calton Hill Observatory in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Once the Royal Observatory moved to Blackford Hill responsibility for the Calton Hill Observatory reverted to the City of Edinburgh Council, who ran it as a popular observatory, available to the public. It was, and is, known as the 'City Observatory'. In 1896 the Council appointed William Peck (1862-1925) as Director. He was a well-known amateur astronomer, telescope maker and author, mostly of popular star atlases. He continued to run the Observatory until his death in 1925. After Peck's death his assistant, John McDougal Field, was appointed Director and ran the Observatory until his own death in 1937.

The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh, an association of local (mostly) amateur astronomers, was founded in 1924 and held the lease on the Observatory from 1938 until 2008, when the increasingly dilapidated state of the buildings obliged them to vacate. Subsequently the buildings have been renovated and leased to the Collective Gallery who operate it as a contemporary art gallery. The historic instruments are all still in situ and complement and contrast the modern art installations.

The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh, an association of local (mostly) amateur astronomers, was founded in 1924 and held the lease on the Observatory from 1938 until 2008, when the increasingly dilapidated state of the buildings obliged them to vacate. Subsequently the buildings have been renovated and leased to the Collective Gallery who operate it as a contemporary art gallery. The historic instruments are all still in situ and complement and contrast the modern art installations.

The Royal Observatory on Blackford Hill

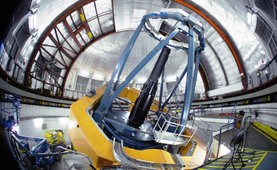

The 36 inch telescope, made by Grubb Parsons, and installed in the East Tower in 1928.

The 36 inch telescope, made by Grubb Parsons, and installed in the East Tower in 1928.

Ralph Copland, the third Astronomer Royal for Scotland, died in 1905. His successors during the first half of the twentieth century were all Cambridge-trained mathematicians, in the same tradition to the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich. Frank Dyson (1868-1939) followed Copland in 1905 and in 1910 resigned to become Astronomer Royal at Greenwich; he is the only person to hold both posts. Ralph Sampson (1866-1939) held the post from 1910 to 1937, retiring at the age of 72. Finally, W.M.H. Greaves (1987-1955) was Astronomer Royal for Scotland during the war and immediate post-war years, 1938 to 1955. During this half-century the Observatory did significant if unobtrusive work in both traditional positional astronomy and stellar astrophysics. In the UK it was a pioneer of objective prism spectroscopy, a photographic technique that allows spectra of all the stars in a star-field to be observed simultaneously, and also of spectrophotometry and photographic photometry. In 1928 this work was facilitated by the installation of a 36-inch reflecting telescope in the East Dome, the larger of the two main domes.

In 1907 the Observatory had become involved in the Carte du Ciel, a major international project that attempted to use photography to map the entire sky. The entire Carte du Ciel enterprise was over-ambitious for the technology then available and did not repay the effort expended on it. However, it marked the Observatory's first foray into photographic sky surveys, a field to which it would make important contributions from the 1960s onwards. During the Second World War the Observatory operated a reserve national time-service, in case the usual service from Greenwich was disrupted by enemy bombing, but in the event this was not needed.

W.M.H. Greaves retired in 1955 and following a short interregnum Hermann Brück was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1957 and held the post until he retired in 1975. This period saw the transition to the modern era. When Brück was appointed the Observatory had about ten staff; when he retired it had about a hundred. The dwelling houses for staff on-site were converted to offices, laboratories and workshops and the first new buildings were added since the initial construction in the 1890s. Professional engineers were recruited to design new instrumentation. Electronics, automation and later computers were introduced. These new techniques allowed, for example, astronomical photographs to be measured automatically, a process that was both much faster and more accurate than earlier manual techniques. Another innovation was the modern Astrophysics degree, which was introduced in 1967.

In 1907 the Observatory had become involved in the Carte du Ciel, a major international project that attempted to use photography to map the entire sky. The entire Carte du Ciel enterprise was over-ambitious for the technology then available and did not repay the effort expended on it. However, it marked the Observatory's first foray into photographic sky surveys, a field to which it would make important contributions from the 1960s onwards. During the Second World War the Observatory operated a reserve national time-service, in case the usual service from Greenwich was disrupted by enemy bombing, but in the event this was not needed.

W.M.H. Greaves retired in 1955 and following a short interregnum Hermann Brück was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland in 1957 and held the post until he retired in 1975. This period saw the transition to the modern era. When Brück was appointed the Observatory had about ten staff; when he retired it had about a hundred. The dwelling houses for staff on-site were converted to offices, laboratories and workshops and the first new buildings were added since the initial construction in the 1890s. Professional engineers were recruited to design new instrumentation. Electronics, automation and later computers were introduced. These new techniques allowed, for example, astronomical photographs to be measured automatically, a process that was both much faster and more accurate than earlier manual techniques. Another innovation was the modern Astrophysics degree, which was introduced in 1967.

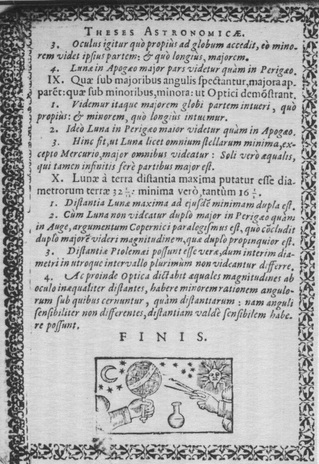

The Observatory's first outstation at Monte Porzio in Italy.

The Observatory's first outstation at Monte Porzio in Italy.

The Observatory opened its first outstation on a high-altitude site at Monte Porzio in Italy, and finally saw the benefits that Piazzi Smyth had demonstrated. This way of working is now ubiquitous. Starting in the 1960s the Observatory also developed instruments that were launched on sounding rockets and artificial satellites, observing from entirely above the atmosphere.

These trends continued under the next two Astronomers Royal for Scotland, Vincent Reddish and Malcolm Longair, who were in post for 1975-80 and 1980-90 respectively. During this period the Observatory was responsible for operating a number of major facilities overseas: the UKST (UK Schmidt Telescope) at Siding Springs, Australia, and the UKIRT (UK Infra-Red Telescope) and later the JCMT (James Clerk Maxwell Telescope), both located on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. The UKIRT and the JCMT were run as national facilities, available for use by all UK astronomers. The principal purpose of UKST was to conduct photographic surveys of the southern sky. The resulting archives of photographs were, and are, stored in Edinburgh. The COSMOS, and later SuperCOSMOS measuring machines, which also operated as national facilities, were developed to rapidly, accurately and automatically measure the photographs.

These trends continued under the next two Astronomers Royal for Scotland, Vincent Reddish and Malcolm Longair, who were in post for 1975-80 and 1980-90 respectively. During this period the Observatory was responsible for operating a number of major facilities overseas: the UKST (UK Schmidt Telescope) at Siding Springs, Australia, and the UKIRT (UK Infra-Red Telescope) and later the JCMT (James Clerk Maxwell Telescope), both located on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. The UKIRT and the JCMT were run as national facilities, available for use by all UK astronomers. The principal purpose of UKST was to conduct photographic surveys of the southern sky. The resulting archives of photographs were, and are, stored in Edinburgh. The COSMOS, and later SuperCOSMOS measuring machines, which also operated as national facilities, were developed to rapidly, accurately and automatically measure the photographs.

Since the granting of its Royal Charter in 1822 the Observatory had operated as a dual institution, comprising the astronomy department of the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Observatory directly responsible to the Crown, with the Astronomer Royal for Scotland holding both the Regius Chair and the Directorship of the Royal Observatory. Since 1965 the authority of the Crown had been exercised by the appropriate Research Council. In the mid-1990s there was a major reorganisation of UK astronomy which significantly changed this arrangement. The Royal Observatory was closed and a new institution founded, the ATC (Astronomy Technology Centre), which was to concentrate exclusively on developing new and innovative astronomical instrumentation. The name 'Royal Observatory Edinburgh' is now used as an umbrella term for all the organisations on site, principally the ATC, the University's Institute for Astronomy and the Visitor Centre. At the same time the post of Astronomer Royal for Scotland would be no longer necessarily associated with either the Edinburgh Regius Chair or the ATC (the incumbent since 1995 has been Prof. John Brown of the University of Glasgow). Subsequently the ATC has played an important role in developing instruments in use in the current generation of ground-based and space-borne telescopes and continues to work on a variety of new projects. Meanwhile the Institute for Astronomy is one of the major UK astronomy groups, pursuing research in a number of fields. It is also heavily involved in current digital sky surveys, which are the successor to the earlier photographic surveys. It continues to teach an Astrophysics degree that is the direct descendant of the one introduced in 1967.

Further Reading

The principal source for the history of the Royal Observatory Edinburgh is H.A. Brück, 1983, The Story of Astronomy in Edinburgh (Edinburgh University Press).

There is relevant material scattered throughout R.M. Birse, Science at the University of Edinburgh 1893-1993, 1994 (Loanhead, Midlothian: Macdonald Lindsay Pindar).

David Gavine, Astronomy in Scotland 1745-1900, 1981 (Open University; PhD thesis) contains a wealth of information on the history of astronomy in Edinburgh and throughout Scotland.

There is relevant material scattered throughout R.M. Birse, Science at the University of Edinburgh 1893-1993, 1994 (Loanhead, Midlothian: Macdonald Lindsay Pindar).

David Gavine, Astronomy in Scotland 1745-1900, 1981 (Open University; PhD thesis) contains a wealth of information on the history of astronomy in Edinburgh and throughout Scotland.